(Poisonous) Plant Highlight: Foxgloves, Digitalis Purpurea

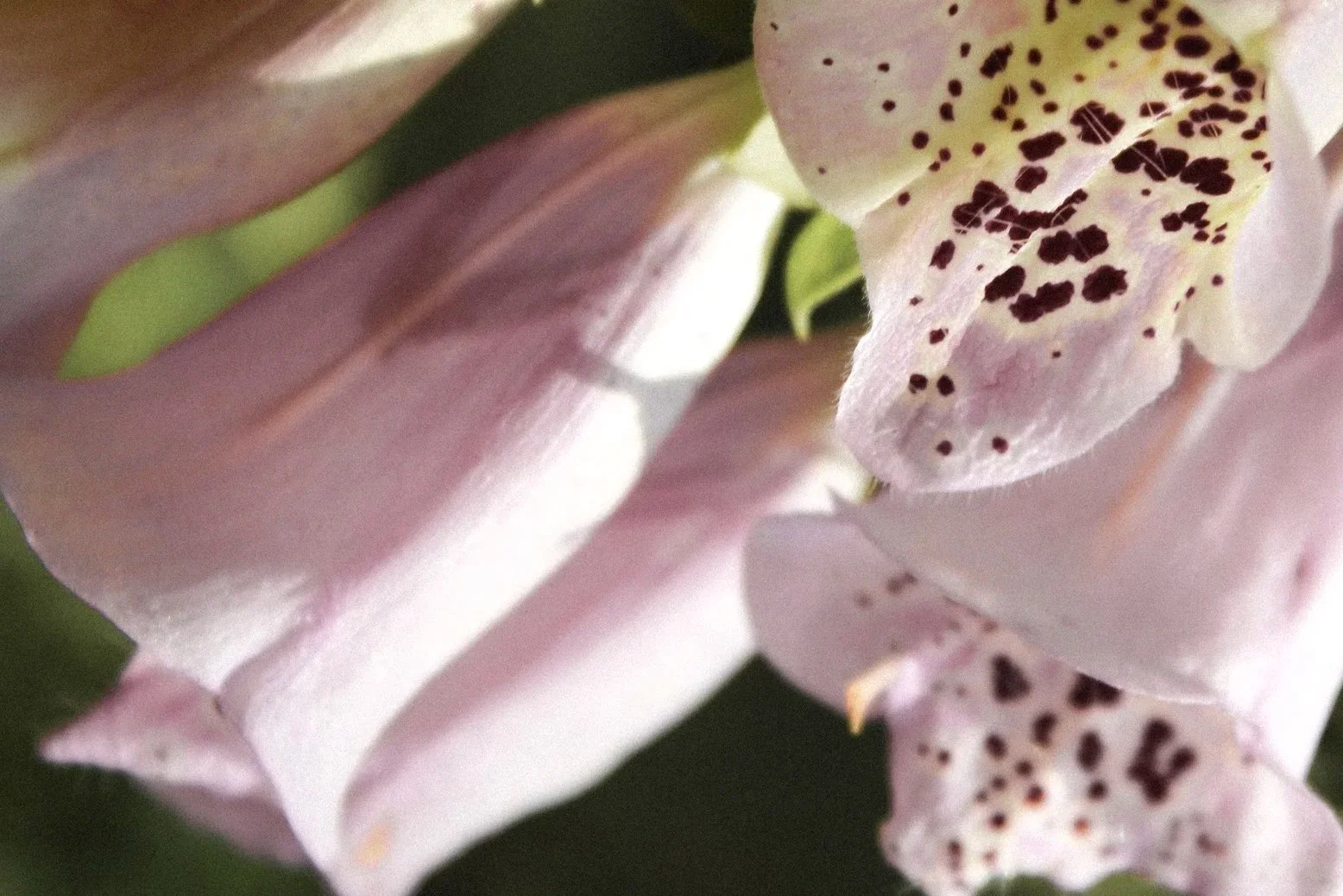

Foxgloves, also known as ‘Folks Glove’, ‘Fairy Glove’, ‘Witches Glove’ ‘Our Lady’s Glove’ and ‘Dead Man’s Bells’ are bell shaped flowers are native to Western and Southwestern Europe, though today they can be found growing in many places in the Northern Hemisphere. The wild flowers are generally purple in color, but we also find pink, red, white, yellow and cream colors in cultivated varieties. Foxgloves can grow to being 5 feet tall which makes them one of the tallest wildflowers. Its latin name, Digitalis, is based on the German name Fingerhut, which refers to finger, digitus, in Latin. Foxgloves belongs to the Plantain family, Plantaginaceae, and the leaves of Foxgloves look much like plantain leaves, with a long and large seed, and a thin and hairy root. They grow primarily in shady and rocky terrains and in the mountains, and bloom primarily in the month of July (though this will be a little dependent on location).

Light Purple Foxgloves

Digitalis Purpurea

FOXGLOVES IN LITTERATURE AND MEDICINE

The first known attestation of Foxgloves in literature appears in the 1542 Historia Stirpium (Research on plants, p. 892) by the German botano-therapist and physician Leonhart Fuchs (1501-1566). At the time Foxgloves were not known by a Greek or Latin name, and so Fuchs created a name, digitalis, based on the German name Fingerhut, which does refer to finger, digitus, in Latin, and proposed for this name to be used until a better name could be found. According to Fuchs, Foxglove’s contain bitter and drying qualities, useful for when a physician would need to cleanse, clear or eliminate matters out of the body. However it is important to note here that foxgloves are considered poisonous, as they contain Digitoxin, a cardiac glycoside that impedes blood circulation and slows down the heart, potentially causing severe symptoms, damage to the body and even death. Though it is also interesting that Digitoxin is also the original source of the heart medicine ‘Digoxin’, used to treat heart failure, arrythmias, and chronic cardiac insufficiency, and Foxgloves have been used, both successfully (and not-so-successfully) by traditional practitioners.

Foxgloves are considered very poisonous, and even accidentally drinking the water from a vase that has had foxgloves in it can cause death to a grown man. Toxic levels of Foxgloves start at only 2.0 nanograms per milliliter of blood, and common symptoms of poisoning include nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and an irregular heartbeat.

«The use of Foxgloves in folk medicine required a steady hand and broad knowledge of its dangers, but it was a preferred plant of Janet Miller, healer from the village of Dundrennan, Scotland. Her knowledge was so in demand that she travelled extensively in her parish to see to her patients, but with her fame came accusations of witchcraft, and she was eventually tried and executed in Dumfries in 1658’. (Botanical Curses and Poisons, Fen Inkwright).

In 1785, the British physician William Withering (1741-1799) published An account of the foxglove and some of its medical uses; with practical remarks on the dropsy, and some other diseases (Birmingham: Swinney). As the story goes, Withering knew of a healer who successfully treated cases of dropsy by administering an herbal tea to her patients. He went to know the plants that were used to prepare tea and discovered later that the major active ingredient was Digitalis. Thanks to its cardio-tonic action, Foxglove was increasing cardiac activity and, as a consequence, drained the body. (https://www.ahpa.org/herbs_in_history_foxglove)

FOXGLOVES AND THE FAIRY FOLK

The folklore and mythology surrounding foxgloves is rich. In particular, Foxgloves have long been assoicated with the fairies, or the faery folk. Many tales also revolve around foxes or gloves, and Foxgloves are known by a plethora of names, including fairy gloves, fairy bells, lady’s glove, bloody bells, witches gloves, dead man’s bells and goblin gloves. In French they are known as Gants Notre Dame, or ‘Our Lady’s Gloves’.

In Norwegian Foxgloves are known as ‘Revebjelle’ directly translated as ‘Fox’s Bell’, and one Norwegian fairytale tells of how the faires taught foxes to ring the bells of a foxglove to warn each other of nearby hunters (Source: Botanical Curses and Poisons, Fen Inkwright).

The common name ‘Folk’s Glove’ also points to the plants relation to the fairy folk- often just referred to as ‘the folk’ in the British Isles and Scotland, and it was thought that the spots on the flower petals of this plant came from where the fairies stood before they took flight. It was also thought that the faeries lives inside of the foxglove’s flowers.

SUPERSTITION

Among the Scottish isles, where the belief in fairies thrived for many centuries, it was a common belief that fairy folk would switch newborn human babies with their own fairy children, known as ‘changelings’ (often with physical deformities). Legends tell of a rather dark way method of ‘forcing’ the fairies to switch back the child; the parents were to smear the juices of Foxglove on the baby’s lips, nose and ears, then placing it on a spade. The faery child was to be flung from the spade three times at dawn, and, if the baby lived, it was considered to be retrieved from the fairy world. If the baby died, which would be a more likely outcome given the intake of Foxglove (not to mention being flung on a shovel!), it was considered lost forever.

Despite Foxglove’s poisonous nature it is believed that planting it in your garden will offer your home protection, and may also attract fairies. In Gaelic language Foxgloves were called Lus Mor, the Great Herb, for being one of the most magical plants. It is said that the reason Foxgloves sway and bend so gracefully is because of the sacredness it has to the fairies, and that it bows to them in recognition. For anyone wanting to work with Foxgloves, it is important to recognize the relationship between this plant and the fairy world, and to know it is a plant to treat with the utmost respect and diligence, being mindful of its potential to both cause harm and kill.